Water features at Quebec City’s City Hall

“Olinda, the Unesco heritage city where I grew up and spent part of my teenage years, was my neighborhood. The house at 208 Côte São Francisco, built at the end of the 19e century and renovated by my architect parents in the 1970s, offered the best living and neighbourhood experience I’ve ever had. As a townhouse, leaning against two others, it showed itself on the street without ostentation with its full foot, and its facade composed of a door and two windows opening directly onto the narrow sidewalk.

With its two steps at the entrance, it was just high enough to avoid the gaze of the many groups of tourists towards our interiors. With its long corridor, it allowed for the distribution of bedrooms and alcoves on the first floor. I don’t know what the layout of the house was like before my parents reformed it, but I do know that their interventions were minimal, notably a generous spiral staircase that brought light and space to the floor below. A cursive-shaped circulation path led around the staircase, through closed rooms and back to the main corridor. For the children, this meant that the space could be used to play hide-and-seek and tag in a loop.

At the far end of the first floor was a lounge and terrace overlooking the backyard, a wooded area, a Dutch fort and the sea.

The house’s double-sash windows, including internal louvred casements, let the sea air circulate through the ceilingless rooms, rising and escaping through the wood and ceramic tile roof, perfect for the hot, humid climate of northeastern Brazil. The interior was lime-painted with heavy brushes; the party walls contained a long crack due to a fault in the structure of the land. Repairs were routine and without final solution, a condition resiliently accepted by my parents and neighbors.

Because of the sloping ground, a floor below contained the kitchen, dining room and access to the walled, stepped backyard. In the backyard, I often played with my brother and two neighbors of the same age. The shape of the courtyard meant that we could see when our neighbors were outside, making it easy to meet up. A carambola tree on the first level of the courtyard was a great place to meet and have adventures. One day, a sloth fell into the unfinished, native plant-covered top landing. The school I attended was on the same street, and all my classmates also lived in the neighborhood, as did my paternal grandmother, who stayed a few streets away in a similar but smaller house than ours. We knew about one family per street in Olinda.

On the same street as ours, a few meters further up the hill, stands a Franciscan monastery. This, along with the city’s dozens of churches, convents and monasteries, were part of our weekend walks. After moving out of this house, my family and I continue to return to Olinda to wander the streets of this fabulous historic site, with which we have a real personal connection.” (Booklet Positive Lived Experiences of Quality in the Built Environment 2024, p.6)

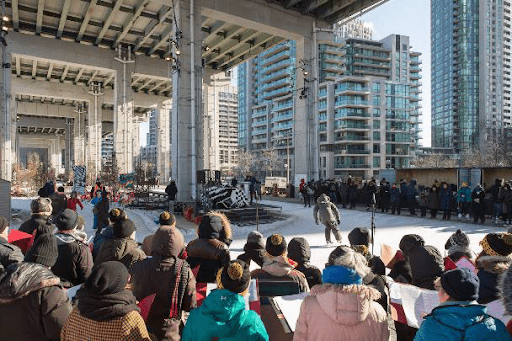

Water features at Quebec City’s City Hall, a contemporary historic site and public park where children play in summer (photo Izabel Amaral).

Discover similar lived experiences